A compassionate explanation of shame through a trauma-informed, neuroscience-based lens.

Shame is quiet, but its voice can echo louder than any other emotion. I remember the first time I truly felt its weight. It wasn’t just the sting of embarrassment or regret. It was the heavy ache that settled deep inside and whispered that something about me wasn’t enough. That kind of shame doesn’t just visit for a moment. It lingers. It reshapes how we see ourselves. And it often arrives long before we even have the words to name it.

For survivors of domestic violence, shame can become a constant companion. It weaves itself into silence, wraps around guilt, and creates a deep feeling of isolation. But shame doesn’t only live in stories of trauma. Every single one of us knows that feeling in some way.

Here’s what I want you to know. Shame isn’t a personal failure. It’s a message from the brain and body. And when we learn how to listen with compassion, we begin to turn shame into healing.

Understanding Shame as a Survival Signal, Not a Personal Failure

Shame is often misunderstood. Because it feels so personal and painful, we tend to believe it means something is wrong with us. But the truth is, shame is not a flaw. It’s a survival response that comes from a deeply human place.

Our brains are wired for connection. Long ago, our survival depended on being part of a group. If we were cast out or rejected, it could mean real danger. So the brain developed mechanisms to help us stay safely connected to others. Shame is one of those mechanisms. It tells us when we might risk losing our place in the group. In that way, shame is the brain’s way of trying to keep us safe.

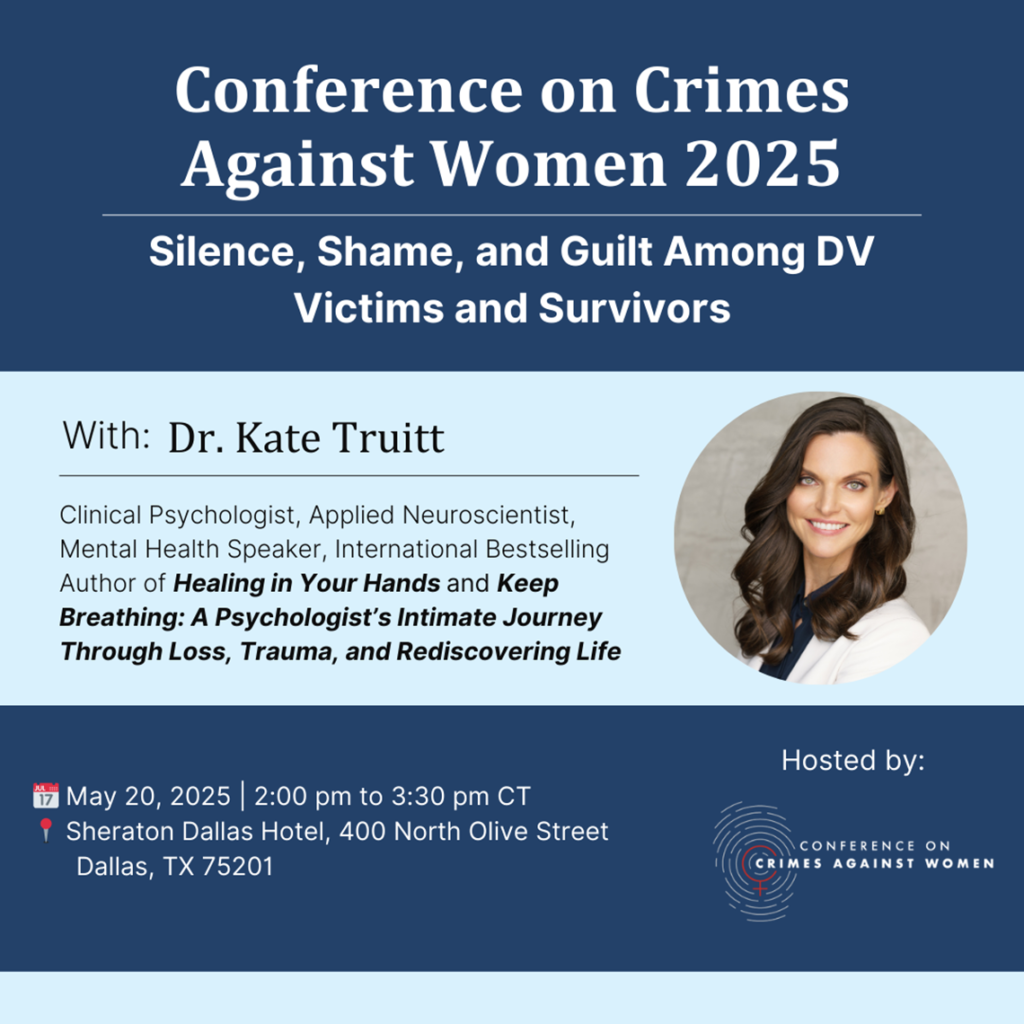

This is one of the core ideas we’ll explore together at the upcoming workshop hosted by Conference on Crimes Against Women, “Silence, Shame, & Guilt Amongst DV Victims & Survivors,” happening on May 20, 2025, from 2:00 to 3:30 PM CT in Dallas B. We’ll take a deeper look at how shame operates in the brain and how to work with it instead of against it.

When we feel shame, the amygdala, the part of the brain responsible for detecting threat, activates. This sets off a stress response and puts the body on high alert. At the same time, the prefrontal cortex, which helps us think clearly and make decisions, becomes less active. That’s why it can feel so hard to think straight when we’re caught in shame.

Understanding that shame is a signal, not a judgment, creates space for compassion. And compassion opens the door to healing.

When Does Shame Become Toxic?

While shame is meant to protect us, it can become deeply harmful when it takes root and goes unchecked. This often happens in the aftermath of trauma. For survivors of domestic violence, shame can become part of daily life. It shows up in the quiet moments, in thoughts like, “Why did I stay?” or “How did I let this happen?” It disguises itself as guilt, silence, or self-blame. Over time, shame doesn’t just visit. It moves in.

Here’s where it gets complicated. The brain doesn’t always distinguish between past danger and present safety. In the short video below, I talk about how past data guide our thoughts and feelings in the present. If someone has experienced repeated harm or emotional abandonment, the brain begins to wire itself around those patterns. Shame becomes a default setting, one the nervous system uses to avoid further pain. It becomes less of a helpful signal and more of a trap that reinforces isolation, low self-worth, and helplessness.

It’s also important to understand the difference between guilt and shame. Guilt says, “I did something wrong.” Shame says, “There’s something wrong with me.” Guilt can be useful. It can guide us to repair. But shame, when left unchallenged, erodes our sense of self.

The Invisible Injuries of Shame

One of the hardest things about shame is that it’s often invisible. You can’t see it on a scan or point to where it hurts in the body, but it leaves deep marks on how we see ourselves and move through the world. Shame doesn’t just hurt emotionally. It can reshape the nervous system, reinforcing patterns of self-doubt, disconnection, and fear.

For survivors of domestic violence, this can feel especially confusing. The brain may still be on high alert long after the danger is gone. The shame that developed as a way to survive now becomes a lens through which the world is seen. It can silence a voice, limit dreams, or keep someone in a cycle of self-protection that feels safe but is also deeply lonely.

The brain’s wiring plays a big part in this. When we experience trauma, the amygdala becomes more sensitive. It’s like a smoke detector that goes off even when there’s no fire. The prefrontal cortex, which helps us make thoughtful decisions and self-reflect, can struggle to stay online in those moments. The body may react with panic, shutdown, or numbness before we’ve even realized what triggered it.

But here’s the empowering truth. These patterns are not permanent. The brain can learn new ways of being. Healing begins when we bring understanding and compassion into the space where shame once lived. With support and the right tools, we can rewrite those invisible stories and come home to ourselves again.

Understanding as the First Step to Healing

Healing from shame begins with a simple but powerful shift: turning toward ourselves with curiosity instead of criticism. When we start to see shame not as proof of our brokenness, but as a message from a brain that has worked hard to protect us, something softens. Compassion enters. And in that moment, healing begins.

The nervous system is always listening. When we’ve lived through trauma, especially something as deeply personal as domestic violence, the brain learns to prioritize safety above all else. Sometimes that means disconnecting from our feelings. Sometimes it means accepting painful beliefs about ourselves just to survive. The brain is doing its job. But survival is not the same as living.

This is where the idea of earned safety becomes important. We can teach the brain, gently and consistently, that the present moment is different from the past. Through practices that engage both body and mind, we can bring the prefrontal cortex back online, soothe the amygdala, and create space for new ways of being.

Shame is such a common thread in the stories of trauma, yet we rarely talk about it openly. That’s why it’s one of the core topics I explore in my book, Healing in Your Hands. In those pages, I walk alongside you as we explore where shame lives in the body, how it affects the brain, and what it means to meet it with compassion. My hope is that those words can serve as a soft landing place for anyone who has ever felt unworthy of healing.

Understanding shame is not about reliving the pain. It’s about reclaiming your story. With each moment of awareness, each breath of compassion, we remind the brain that it is safe to feel, safe to grow, and safe to be seen.

Three Gentle Tools to Begin Reclaiming Your Voice

Understanding shame is a powerful first step. Taking action from a place of self-compassion is what helps the healing take root. These practices are simple, but their impact can be profound. Each one helps send a new message to the brain and body: You are safe now. You matter. You belong.

- Name the Shame

Shame thrives in silence. When we give it a name, we take away its power. Try simply saying to yourself, “This feels like shame,” when the emotion shows up. That moment of recognition activates your prefrontal cortex and begins to regulate the nervous system. Awareness is the first step to reclaiming your voice. - Anchor in the Body

Shame can feel like disconnection. Bring yourself back to the present by grounding in the body. Place a hand on your heart, take a slow breath, or gently press your feet into the floor. These small actions remind your brain that you are here and you are safe. They bring the body into a state where healing becomes possible. - Speak with Kindness

Talk to yourself the way you would speak to a friend or loved one. Try phrases like, “This is hard, and I’m doing the best I can,” or “It makes sense that I feel this way.” These compassionate statements rewire the brain’s inner dialogue and help build a foundation of self-trust. In the guided meditation below you can connect with your inherent sense of self-love, compassion, and caring.

Healing doesn’t require perfection. It begins with small, repeated moments of care. These practices are a way of saying to yourself, “I am worthy of gentleness. I am allowed to heal.”

There’s Nothing Wrong With You — There’s Just a Wound That Deserves Care

Shame is not who you are. It is something you’ve experienced, something your brain and body learned in response to pain. When we begin to understand that shame is not a flaw but a signal — a call for care, connection, and compassion — we can stop running from it and start healing through it.

Healing is not about forgetting what happened. It’s about remembering who you are beneath the survival strategies. It’s about coming home to your worth, your voice, and your power. The path forward is not linear, but it is possible. And you do not have to walk it alone.

If this conversation resonates with you, I invite you to join me for a deeper exploration of these ideas in my upcoming workshop:

Together, we’ll explore the neuroscience of shame, the impact of trauma on identity, and the powerful tools that help survivors reclaim their voice and their healing. Let’s rewrite the story that shame tried to tell — and replace it with one of compassion, courage, and hope.

Together, we’ll explore the neuroscience of shame, the impact of trauma on identity, and the powerful tools that help survivors reclaim their voice and their healing. Let’s rewrite the story that shame tried to tell — and replace it with one of compassion, courage, and hope.

To support your healing journey, explore this free resource that I created: SHAPED Framework Self-Discovery Worksheet. Created with care and intention, this worksheet is grounded in neuroscience and designed to help you embrace healing, clarity, and authentic living.

You are not alone. You are already enough. And your healing journey is worthy of care.

And if someone you love is carrying silent shame, please consider sharing this with them. Sometimes a single moment of connection is all it takes to begin again.

References:

- JBWS. (n.d.). Why won’t victims of abuse just leave? Understanding the shame and complexity of domestic violence. https://jbws.org/news/why-wont-victims-of-abuse-just-leave-understanding-the-shame-and-complexity-of-domestic-violence/

- Smith, M. E., & Segal, J. (n.d.). Domestic violence and abuse. HelpGuide. https://www.helpguide.org/relationships/domestic-abuse/domestic-violence-and-abuse

- Trauma Support Team. (n.d.). Shame and guilt. https://tstresources.org/shame-and-guilt/

- Campbell, D. (n.d.). Peeling the onion of abuse and shame. https://www.drdebracampbell.com/peeling-onion-abuse-shame/